At Christmas, when I told my sister I was going to see Van Morrison January 16th, she half-joked “Is he still alive?”

Since then, we have had the passing of David Bowie, Glenn Frey of the Eagles, and Lemmie Kilmister (of Motorhead) in just a short time. It seems odd but there may be an explanation.

The phenomenon of dying after the holidays is well known as people tend to hang on then experience an existential ‘let down’ during which time, their will to live can wane.

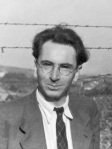

So how important is our will to live in sustaining us? According to Viktor Frankl, the author of “Man’s Search for Meaning” and the founder of a third Viennese school of psychotherapy, LOGOTHERAPY, a meaning for living is primary above all else.

Frankl describes the first school of Freudian therapy as obsessed with the ‘pleasure principle’ but as the principle of HEDONIC ADAPTATION and Buddhist philosophy tells us, the pursuit of pleasure is fleeting. Once you get that sixth car, you no longer can desire it.

Secondly, there is the Adlerian school, where the individual strives to overcome feelings of inadequacy by attaining mastery and a will to power.

But Frankl, a Jewish Viennese Neuropsychiatrist who survived six months in four different Nazi Concentration camps and then wrote about his experiences, states that meaning is the most fundamental driving force for survival. He recounts how the death rate increased after Christmas and New Year’s Day because he believes many of the prisoners made mental bargains with themselves to hold on until the holidays.

Frankl describes a certain syndrome where some who were living in that existential hell of concentration camp life, that “provisional existence of unknown duration”, would ‘snap’ and simply stop getting up in the morning and lie in their own filth until they succumbed. He describes how their immune systems just gave up and and particularly eerie and ironic anecdote of a man who in a dream was told that March 30, 1945 would be the end of his suffering in the concentration camp. When that day came without reprieve, he fell into illness as self-fulfilling prophecy and died the day after.

Frankl concludes that whether in a concentration camp, or in the provisional existence of unknown duration that we all experience as life, humankind needs to create meaning and that without it, the human animal cannot find the strength to maintain its own spiritual, energetic, immunological, or existential inertia.

So what is the conclusion that Dr. Frankl reaches about man’s ultimate search for meaning that sustains us? Interestingly, it is not internal or cosmological but rather external and concrete. He states that from moment to moment, a person should live as though this were the second time around and that the first time, they made some horrible mistakes like the ones they are currently contemplating.

Frankl says that we are charged not with asking “what is the meaning of life generally” but rather “what is life asking of me specifically at this moment?” He suggests that we are tasked with forging meaning in life by:

- By creating a work or doing a deed

- By experiencing something or encountering someone

- By the attitude we take toward unavoidable suffering

For Frankl, the goal of living is not happiness per se, which is fleeting and perhaps a kind of set point known as the Hedonic Adaptation principle, but rather a matter of existential necessity in asking how best to be of service, be kind, and show dignity in the face of unavoidable suffering.

In some ways, we are all living in a hopeless concentration camp at this moment in history because so few of us believe in a reprieve from this “provisional existence of unknown duration”. Most are given to gallows humor, fatalism (literally and figuratively), and distractions of seeking pleasure and power.

Although the infamous sign above the entrance to Auschwitz read “Arbeit macht frei” – or ‘work will make you free” was a cynical platitude meant to incite more productivity from the condemned, Frankl’s own work ironically lends some credence to that slogan for all of us living out our apparent death sentences in a life beset by aging, chronic debilitating disease, and impending cancer. Logotherapy suggests that only the work of our lives can free us from the hopelessness of despair that is a secular, objective, and materialistic world in which most of us accept aging gracefully and dying in our sleep as the highest aspirations possible.

I thought it particularly pithy that one of Frankl’s notions was that “self-actualization is only possible with self-transcendence”. As an example, he explains that the ability to laugh at oneself is essential to rising above our own prisons of ego neurosis and as I blogged about here, perhaps laughter is the best medicine when it comes to staying young for just that reason.

Postscirpt:

I and many of my patients now have internalized the idea of living well past a normal lifespan via telomerase activation and adaptogens, but interestingly, that doesn’t change the geometry of our search for meaning appreciably. As you can read in this blog, the choices that face would-be immortals don’t change much.

1 thought on ““Is he still alive?” Gallows humor and the concentration camp of life”

Pingback: Archives Week 7- May 15, 2022 – Recharge Biomedical